(Unless otherwise stated, the copyright of the materials included belong to Jan Woreczko & Wadi.)

Szablon:Woźniak (2021, ASMP)

Z Wiki.Meteoritica.pl

m |

m |

||

| Linia 24: | Linia 24: | ||

<gallery caption="" widths="200px" heights="200px" perrow="3"> | <gallery caption="" widths="200px" heights="200px" perrow="3"> | ||

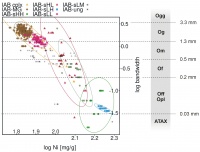

| - | File:Iron_meteorites_classification_(trace_elements_Ni-Ge).jpg| | + | File:Iron_meteorites_classification_(trace_elements_Ni-Ge).jpg|Para pierwiastków nikiel i german jest silnie skorelowana oraz ma silne własności dyskryminujące. Wykres ten ilustruje również początkową ideę podziału meteorytów żelaznych na grupy ponumerowane rzymskimi liczbami I-IV (''Nickel vs. germanium diagram, the strong, positive correlation is visible. This diagram illustrates the early idea of iron meteorites classification groups, numbered by the use of Roman numerals I-IV'') |

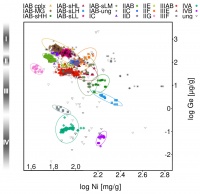

| - | File:Iron_meteorites_classification_(trace_elements_Ga-Ge).jpg| | + | File:Iron_meteorites_classification_(trace_elements_Ga-Ge).jpg|Para pierwiastków gal i german jest silnie skorelowana oraz ma silne własności dyskryminujące. Wykres ten ilustruje również początkową ideę podziału meteorytów żelaznych na grupy ponumerowane rzymskimi liczbami I-IV (''Gallium vs. germanium diagram, the strong, positive correlation is visible. This diagram illustrates the early idea of iron meteorites classification groups, numbered by the use of Roman numerals I-IV'') |

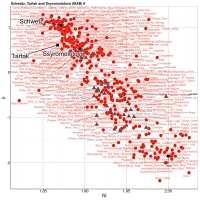

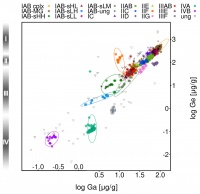

| - | File:Iron_meteorites_classification_(trace_elements_Ni-Ir).jpg | + | File:Iron_meteorites_classification_(trace_elements_Ni-Ir).jpg|Para pierwiastków nikiel i iryd (''Nickel vs. iridium diagram'') |

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

Wersja z 19:42, 17 lip 2021

Woźniak Marek, (2021), Meteoryty żelazne – klasyfikacja w obrazach (Iron meteorites – classification in pictures), Acta Soc. Metheor. Polon., 12, 2021, s. 149-216. Plik ASMP (abstrakt).

Abstract: Iron meteorites are meteorites whose main constituent is iron (Fe) and nickel (Ni), which occur in two forms of Fe-Ni minerals – kamacite and taenite. Since their composition makes them more resistant to shattering (crushing), and they are more challenging to ablate when passing through the atmosphere, they statistically fall in the form of larger lumps than stone or iron-stone meteorites. Their metallic structure and highly high weight make them easy to distinguish from ordinary rocks. The mass of all known iron meteorites is over 500 tons, which is ~89% of known meteorites, but falls of iron meteorites account for only 4.56% of all observed falls (wiki.meteoritica.pl). The ten largest meteorites in the world are iron meteorites! In the past, the term siderite was used to describe iron meteorites.

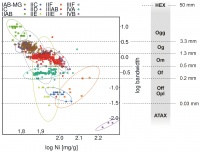

The classification of iron meteorites is based on two criteria. The older method is based on the average nickel content and the crystal structure revealed on cut and etched surfaces, the so-called the Thomson-Widmanstätten patterns. In this division, we distinguish three groups: hexahedrites (4–6 wt.% Ni), the most popular octahedrites (6–12 wt.% Ni) and ataxites (>12 wt.% Ni).

The second, more recent method of classifying iron meteorites is based on their chemical composition, in particular the content of trace elements such as germanium (Ge), gallium (Ga), platinum (Pt), arsenic (As), gold ( Au) and iridium (Ir). Another parameter that defines the groups of iron meteorites is their mineral composition. “Indicator” minerals are in the form of various compounds and multiple shapes and sizes: sulfides, phosphides, carbides, nitrides, and silicate inclusions. Trace element content versus nickel content reveals chemical clusters representing the different chemical groups of iron meteorites. Some of the iron meteorites come from the partially differentiated asteroid ruptured at the beginning of forming the iron core and the silicate-rich shell (these are groups IAB and IIE). The remaining meteorites from other groups come from the nuclei of minor differentiated asteroids, shattered in collisions shortly after formation.

Keywords: iron meteorites, classification, trace elements, hexahedrites, octahedrites, ataxites, parent body, cooling rate, meteorite mineralogy, Morasko, Tartak, Schwetz, Seeläsgen, Tabarz

Relacja między zawartością niklu a szerokością belek kamacytu w meteorytach żelaznych (z wyłączeniem podgrup grupy IAB) (Relation between the nickel content and the kamacite lamellae size in iron meteorites (excluding the IAB subgroup)) |

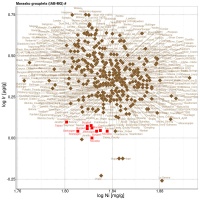

Para pierwiastków nikiel i german jest silnie skorelowana oraz ma silne własności dyskryminujące. Wykres ten ilustruje również początkową ideę podziału meteorytów żelaznych na grupy ponumerowane rzymskimi liczbami I-IV (Nickel vs. germanium diagram, the strong, positive correlation is visible. This diagram illustrates the early idea of iron meteorites classification groups, numbered by the use of Roman numerals I-IV) |

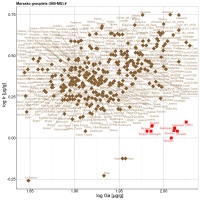

Para pierwiastków gal i german jest silnie skorelowana oraz ma silne własności dyskryminujące. Wykres ten ilustruje również początkową ideę podziału meteorytów żelaznych na grupy ponumerowane rzymskimi liczbami I-IV (Gallium vs. germanium diagram, the strong, positive correlation is visible. This diagram illustrates the early idea of iron meteorites classification groups, numbered by the use of Roman numerals I-IV) |