(Unless otherwise stated, the copyright of the materials included belong to Jan Woreczko & Wadi.)

Lamele Breziny i Reichenbacha

Z Wiki.Meteoritica.pl

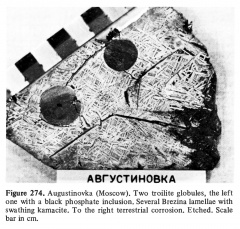

Na wytrawionych przekrojach wielu meteorytów żelaznych widać charakterystyczne wąskie, długie struktury. Są to inkluzje schreibersytu (lamele Breziny) i troilitu (lamele Reichenbacha) otoczone kamacytem z domieszkami innych faz.

Podczas przelotu meteoroidu przez atmosferę w wyniku ablacji przypowierzchniowe fazy mineralne (inne niż dominujący stop żelazo-nikiel) ulegają intensywniejszemu wykruszeniu/wypłukaniu. Tworzą się wówczas na powierzchni meteoroidu/meteorytu wgłębienia po nodulach troilitowych oraz liczne wydłużone wgłębienia (długie nawet na kilka centymetrów, szerokie i głębokie na kilka milimetrów) przypominające ślady po dłucie (blizny) pochodzące od wykruszonych inkluzji schreibersytu i troilitu. Inkluzje składające się ze schreibersytu nazywa się lamelami Breziny, natomiast te zbudowane głównie z troilitu nazywa się lamelami Reichenbacha (oba te określenia są obecnie używane rzadko w opisach cech fizycznych meteorytów żelaznych).

Oba typy lamel najczęściej występują w meteorytach żelaznych typu IIIAB. Tak je opisuje Rubin et al. (2021, s. 187):

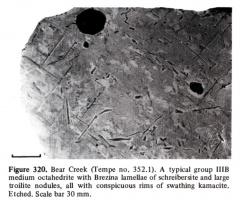

IIIAB: This the largest magmatic iron group; most members are medium octahedrites (Om); others are fine (Of) or coarse (Og) octahedrites. The principal minerals are kamacite, taenite, and plessite. In many specimens, kamacite contains numerous small rhabdites, platelets of carlsbergite, and rare grains of daubréelite. Low-Ni IIIAB irons contain troilite with small rhabdite inclusions; high-Ni specimens contain elongated oriented troilite inclusions (Reichenbach lamellae) and oriented schreibersite crystals (Brezina lamellae) occurring parallel to (100, (210), (211), and (110). (…)

Lamele Breziny

Lamele Breziny (ang. Brezina lamellae) są to wielocentymetrowej długości i milimetrowej szerokości listwy (ang. laths) schreibersytu. Nazwa pochodzi od ich odkrywcy Aristidesa Breziny. Lamele te są doskonale widoczne, np. w wielu okazach meteorytu Morasko[2] i na powierzchni meteorytu Hraschina.

Tak opisuje lamele Breziny m.in. w meteorycie Hraschina Buchwald (1975, s. 667) (wyróżnienia w tekście Redakcja):

(…) The morphological differences between the two sides correspond closely to what may be observed on, e.g., Ilimaes[3], Cabin Creek[4], Iron Creek and Quinn Canyon. The reason must be the same, i.e., the meteorites represent highly oriented stabilized falls where the convex, deeply carved surface was foremost during the flight. On both surfaces, but distinctly on the anterior one, straight scars resembling chisel marks may be observed. They are typically 1-5 cm long and 1-2 mm deep and wide, and are apparently oriented in a limited number of directions. They indicate where Brezina lamellae of schreibersite were partly removed by ablation melting during the atmospheric flight. (…)

Schreibersite is common as imperfect Brezina lamellae in dodecahedral directions. They range in size from 50×1 mm to 2×0.2 mm and are enveloped in 0.8-1.0 mm wide rims of swathing kamacite. (…)

Występowanie lamel Breziny opisuje Buchwald również, np. w meteorytach Needles (typu IID, Of) (Buchwald 1975, s. 886) i Grant (typu IIIAB, Om).

Lamele Breziny

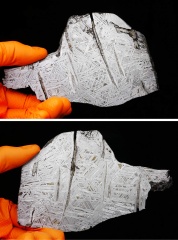

Meteoryt Bear Creek (IIIAB, Om) (źródło: Buchwald 1975) |

Meteoryt Bear Creek (IIIAB, Om) (fot. Donald Hurkot) |

|

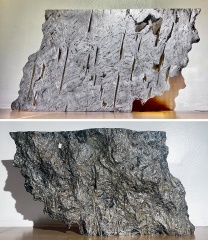

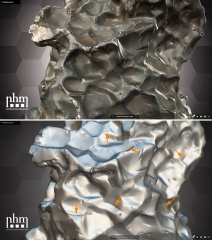

Fragment powierzchni meteorytu Hraschina z kilkoma widocznymi lamelami Breziny (pomarańczowe strzałki) (model 3D; wypukły „przód”; patrz → Hraschina/Galerie) |

Meteoryt Narraburra[1] (IIIAB, Om) (źródło: Liversidge 1903) (więcej patrz → Liversidge (1903)) |

|

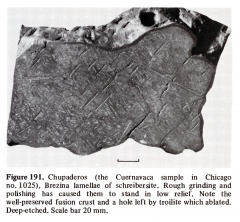

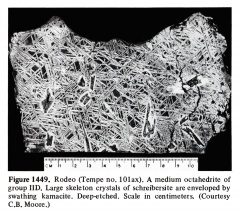

Meteoryt Rodeo[8] (IID, Om) (źródło: Farrington 1905) |

Meteoryt Rodeo[8] (IID, Om) w kolekcji Muzeum Historii Naturalnej w Pradze (Prague Natural History Museum) (fot. Tomasz Jakubowski) |

Meteoryt Saint-Aubin (IIIAB, Om); doskonale widać lamelę na powierzchni okazu (fot. Lech Kurnicki) |

Lamele w meteorycie Saint-Aubin (IIIAB, Om) (fot. Lech Kurnicki) |

Meteoryt Santo Antônio do Descoberto (IIAB, HEX) (fot. Zsolt Kereszty) |

Lamele Reichenbacha

Lamele Reichenbacha (ang. Reichenbach lamellae) występują w meteorytach żelaznych. Są to wydłużone inkluzje składające się głównie z troilitu. Pierwszy ich typ jest dłuższy i węższy (do 6 cm i 0,2 mm) zawiera troilit z podrzędnym daubréelitem i jest zwykle otoczony schreibersytem i kamacytem. Drugi typ jest krótszy i grubszy (do 2 cm i 3 mm) składa się głównie z troilitu z daubréelitem oraz rzadkimi ziarnami grafitu i krzemianu. Często lamelą towarzyszą kryształy chromitu. Wydaje się, że meteoryty zawierające inkluzje troilitowe drugiego typu stygły szybciej niż większość meteorytów żelaznych. Nazwa od ich odkrywcy Karla Ludwiga Friedrich Freiherr von Reichenbach.

Tak opisuje lamele Reichenbacha Buchwald (1975, s. 108):

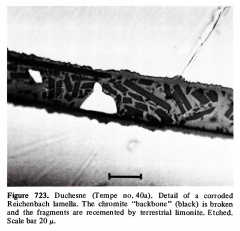

Reichenbach lamellae were seen by Reichenbach (1861, etc.) and named by Brezina (1880b). When best developed, they form very thin (<0.05 mm), but large (20×30 mm) platelets in three directions parallel to {100}γ. Additional directions are often present, e.g., in Cape York.[9] Unfortunately, the lamellae are difficult to examine because they are thin and often broken and easily corroded. Usually when the present author has had a well-preserved Reichenbach lamella under the microscope and under the microprobe, it surprisingly turned out that the lamellae were not, as hitherto believed, pure troilite lamellae but were composed rather of primary, ultrathin (1-5 μ) chromite lamellae upon which secondary troilite had later nucleated. In other words, the chromite must have determined the crystallographic relationships with the taenite and the formation must have taken place at a considerably higher temperature and because of a different mechanism than that proposed by Brett & Henderson (1967). It can, however, not be ruled out that some Reichenbach lamellae consist only of thin troilite sheets and can have formed as crack-fillings (Brett & Henderson 1967).

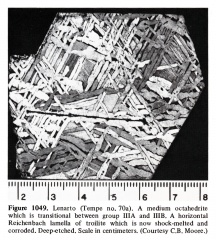

Lamele Reichenbacha zaobserwowano m.in. w meteorytach Lenarto, Teplá (patrz → Buchwald 1975).

Lamele Reichenbacha

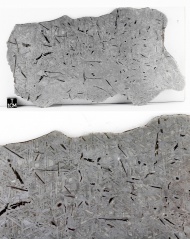

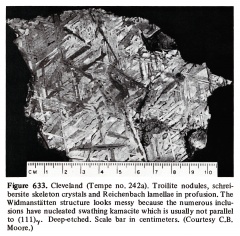

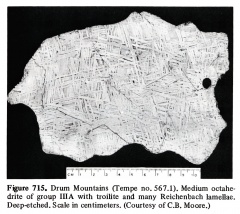

Meteoryt Drum Mountains (IIIAB, Om) (źródło: Buchwald 1975) |

||

O zaobserwowaniu lamel troilitu w płycie meteorytu Hraschina wspomina Brezina (1885, s. 209) Schreibers 1820) |

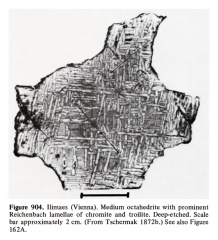

Meteoryt Ilimaes (iron)[3] (źródło: Buchwald 1975) |

|

Bibliografia

- Brezina Aristides, (1882), Über die Reichenbach'schen Lamellen in Meteoreisen (Mit 4 Tafeln), Denkschriften der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 43, Abt. 2, 1882, s. 13-16.[10] Plik PDF.

- Brezina Aristides, (1885), Die Meteoritensammlung des k. k. mineralogischen Hofkabinetes in Wien am 1. Mai 1885 (Mit vier Tafeln (Nr. II-V).), Jahrbuch der Kaiserlich-Königlichen Geologischen Reichsanstalt, 35, 1885, s. 151-276, (s. 209) (ilustracje).[11][12] Plik DjVu.

- Brezina Aristides, Cohen Emil Wilhelm, (1886), Die Structur und Zusammensetzung der Meteoreisen: erläutert durch photographische Abbildungen geätzter Schnittflächen, Lieferung I, Stuttgart 1886.

- Brezina Aristides, Cohen Emil Wilhelm, (1887), Die Structur und Zusammensetzung der Meteoreisen: erläutert durch photographische Abbildungen geätzter Schnittflächen, Lieferung II und III, Stuttgart 1887.[13]

- Brezina Aristides, (1904), Über dodekaedrische Lamellen in Oktaedriten, Sitzungsberichte der mathematisch-naturwissenschaftliche Classe der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 113, 1881, s. 577-583.[14] Plik DjVu.

- Buchwald Vagn Fabritius, (1975), Handbook of Iron Meteorites. Their History, Distribution, Composition, and Structure, University of California Press, Berkeley 1975, (s. 105, 107, 108, 122, 280, 478, 542, 614, 667, 765, 883, 1186). ISBN 0-520-02934-8.[15] Pliki PDF.

- Liversidge Archibald, (1903), The Narraburra meteorite, Journal and proceedings of the Royal Society of New South Wales, 37, 1903, s. 234-242.[1][16] Plik DjVu.

- Perry Stuart H., (1944), The metallography of meteoric iron, Bulletin of the United States National Museum, Smithsonian Institution, 184, 1944, ss. 206, (s. 167) (9 figs, 78 pls.).[17] Plik doi.

- Reichenbach Karl Freiherr von, (1861), Ueber das innere Gefüge der nähern Bestandtheile des Meteoreisens (XV. VI. Das Elektro-Galvanometer; vom Inspector Meyestein in Gottingen. XVI. Das Badeisen. XVII. Das Fülleisen. XVIII. Die Wülste und das Glanzeisen), Annalen der Physik, 114, Bd. 190, 1861, s. 99-132, 250-274, 477-491 (ilustracje).[18] Plik DjVuŹródło: Wiki.Meteoritica.pl.

- Roy Sharat Kumar, Wyant Robert Kris, (1950), The La Porte meteorite, Field Museum of Natural History, Geological Series, vol. VII, no. 10, 1950, s. 135-144. Plik DjVu.

- Rubin Alan Edward, Ma Chi, (2021), Meteorite Mineralogy, Cambridge University Press, 2021, ss. 418. Plik doi.

- Spencer Leonard James, (2018), ‘Reichenbach’ and ‘Brezina’ lamellae in meteoritic irons, Mineralogical Magazine, 29(213), 2018, s. 545-556. Plik doi.

- Woźniak Marek, (2021), Meteoryty żelazne – klasyfikacja w obrazach (Iron meteorites – classification in pictures), Acta Soc. Metheor. Polon., 12, 2021, s. 149-216 (abstrakt).[19] Plik ASMP; Książka abstraktów.

Przypisy

Zobacz również

- meteoryty: Hraschina (Hraschina/Galerie), Lenarto, Teplá

- Buchwald (1975)

- Liversidge (1903)

- Bibliografia/Brezina Aristides

- Bibliografia/Reichenbach Karl Freiherr von

Linki zewnętrzne

- woreczko.pl – Ablacja (Ablation) ● Meteoryty żelazne – klasyfikacja w obrazach (Iron meteorites – classification in pictures) ● Minerały w meteorytach (Meteorite minerals) ● Słownik „meteorytowy” (Glossary)

- Cambridge University Press – ‘Reichenbach’ and ‘Brezina’ lamellae in meteoritic irons